PRD Governments and Health in the Federal District:

An Incomplete Process

Gustavo Leal F.

Departamento de Atención a la Salud

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Xochimilco

October 2012

Executive Summary

The PRD’s debt with the people of Mexico City

The governments of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) have an outstanding debt with Mexico City’s population that lack coverage by social security: to guarantee under similar need, their right to integral health protection, after the majority of the capital’s electorate put its confidence in the PRD to transform the life conditions of the residents of this jurisdiction.

Achieving sustainability of healthcare for the residents of Mexico City constitutes a great challenge for whoever wants to run its government, given the clearly insufficient network of services (hospitals, clinics, and health centers) and a context in which policies for preventing health risks have much room for improvement.

Coming in and out of the metropolitan network are users and patients from at least two surrounding states: the State of Mexico (EDOMEXincluding the local Secretariat of Health and the Social Security Institute of the Mexico State and Municipalities-ISSEMYM); as well as the state of Morelos

.

But above all, the efforts to substantive improve Mexico City’s health services crash with the institutional structure responsible for the task; structure that results from the peculiar administrative and political nature of the Government of the Federal District (GDF), established only in 1997.

Other factors aggravating the insufficiency of the capital’s health services are: the demand of a heterogeneous and polarized city with a high degree of informality; a citizenry impoverished by recent economic policies; the city’s floating population; large poor and marginalized areas; and the indigenous population that resides in it.

Equally burdensome to the capital’s health institutions is the fact that they are surrounded and coexist with the powerful federal health network: IMSS-SSA-ISSSTE-ISSFAM-SEDENA-PEMEX.

In size and importance, the medical network of the GDF ranks fourth at the federal level, surpassed only by IMSS, SSA and ISSSTE, and followed by PEMEX medical services.

Fourteen years after the left won the elections for chief of government of the DF and after important yet insufficient reforms, the population of the capital has observed the lack of creativity shown by governments coming from the PRD to design its own legal and health related order, an order capable to begin to satisfy the city’s health demands, at the margin of the vast federal structure seated in the capital of the Republic.

Why is the metropolitan health network unique?

Known from the 1980’s as the Medical Services of the DDF and, starting in 1997, as the Secretariat of Health of the GDF it has been built on top of, sideways, and sharing the aforementioned federal structure. Additionally, the network is casted in the city where the heart of national decision-making is located, in the city of centralism by antonomasia: the Federal District. This was the emblematic city of the prolonged dominance of the one party, the PRI which governed uninterruptedly for 70 years.

During those eighties, and still under the hegemony of the PRI, a group of officers trained in the health strategies of the British National Health Service (NHS) experimented with an adjustment of the Medical Services of the DDF. Their main purpose was to establish a tiered system of care for the DF in coordination with the SSA which in those years, had not yet formalized a process of decentralization. They were also aiming to advance the National Health System.

It was until 1997 that the Government of the Federal District was born, and with it the full powers of its Legislative Assembly (ALDF), its Judiciary, as well as its administrative apparatuses, one of them being the Secretariat of Health of the GDF.

An exceptional political statue

Many of the problems facing the responsiveness of the health network arise, rest, and come from the DF’s unique political and administrative organization. They derive from that original condition.

As the seat of the federal powers, the political organization of the Federal District is unique and different from the 31 states that comprise the federation.

It is clear that after those 14 years and despite their absolute legislative majorities in the ALDF, the administrations of the left have been unable to make point and submit to ample public debate the political statue that, for its importance and weight on the Federation, holds the DF. With the time, this has caused a delay on the awaited improvements of its public policies, among them those of health and social security.

Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas: first chief of government (1997-2000)

The engineer Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas received a legal structure the main objective of which was to maintain the hegemony and control of the President of the Republic over federal programs as the public policies of the DF were applied. The inheritance ranged from the legislation that gave the capital’s government the figure of a Regent, to other ordenances that kept this government within the orbit of the Federal Executive Branch.

The headquarters of the federal powers, the DF was largely governed from the Presidency. On August 10, 1987 the DF’s Assembly of Representatives was born as a representative body for the citizenry. A vast movement of grassroots organizing had emerged immediately after the earthquake of 1985 which forced the hegemonic group to break the stronghold that had contained the democratic aspirations of the capital’s people.

The Assembly held powers to dictate decrees, ordinances and rulings, as long as the legislative faculties relating to the Federal District remained in the hands of the National Congress. It was composed by 40 members elected by majority vote, and 26 by proportional representation.

By January of 1987 a Health Law of the DF had been issued.

In 1993, Congress issued the Statute of the Government of the DF, which gave more powers to the Assembly. But is wasn’t until 1996, through a new constitutional amendment, that the figure of Chief of Government of the DF was established and the designation of the DF’s administration officials, which had been the responsibility of the president of the Republic, was modified, making the Chief of Government and the 16 delegational chiefs be elected by popular vote.

The Assembly became the Federal District Legislative Assembly (ALDF) advancing in its function as local parliament. This reform maintained the sui géneris quality of the state, treated differently than the other 31 states of the Federation. It remained in the hands of the president of the Republic the power to appoint who has the direct command of the DF’s enforcements; the power to propose to the Senate who would be successor, in case the Chief of Government is removed; the power to establish the amount of borrowing for the financing of local expenditures; the power to initiate legislation before Congress on matters pertaining to the DF; and to publish the laws pertaining to the DF that Congress itself had issued.

The next step was the election by way of popular vote of the first governor of the Federal District, an honor bestowed on Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, postulated in 1997 by the PRD, who conducts the first programmatic design, even though the local administration remained captive and surrounded by the logic of the federal programs.

In matters of health policy, his administration coincided with the decentralization of services applied by the federal government to the GDF between 1997 and 2000: Coordinating agreement for the decentralization of health services for the general population of the Federal District.

The lack of a timely correction -during the process of divestiture and its later decentralization- of the imbalance between the budgetary allocation of the Secretariat of Health of the DF and that of the Directorate General of Public Health Services of the DF-derived from the federal decentralization- resulted in lags in Primary Care that persist today and continue to affect its availability, as well as an insufficient coordination between Primary and Secondary Care, despite the later having now more economic resources available. A good part of the problems weighing on the health services network derives from that original condition.

In the Secondary Level staffing arrangements and the provision of care supplies and materials remain outdated, generating waste and recurrent improvisation in the processes of patient care. All this also has an impact on the hefty corporate heritage of the sector’s labor unions and contributes to delay the urgent modernization of their proposals as they pertain to labor matters.

The impacts fall directly upon the quality of care, which among other things, is achieved by the adequate number of medical, nursing, and allied personnel, capable of responding to the qualitative and quantitative demands of the patients and users of services.

Would have PRI or PAN done it “better”? What was anticipated from Cárdenas as a first administrative design, was a lot more imagination. In matters of health, this effort should have been assumed by Dr. Armando Cordera Pastor, secretary of health during that period.

The results of the Cárdenas administration did not meet the expectations generated by a change in the provision of services. There was no innovation and no integration of new talents into public management, something that his successors were to add, basically by reaching out to resources trained in public universities.

The subsequent programs of austerity that were to be organized by the administrations of Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Marcelo Ebrard contributed to increase the pressure on the operative staff which is, in the end, the one that makes health institutions function effectively.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2000-2005)

The second DF government clearly veers to the left setting off a package of new social programs, among them a universal pension. It utilizes the acquired public administration to stamp a new political twist: ample social programs, increase taxation, public infrastructure, transparency in the use of resources, and incorporation of new talents from academic and social sources.

López Obrador is also a Chief of the DF with political fortune. His period coincides with the first PAN federal government. He uses this alternate party situation in his favor and diminishes the PRI politically, despite a lesser control over the Delegations, as compared with Cárdenas.

Since 2003, the diagnoses of the local Secretariat of Health concern the state of the health network:

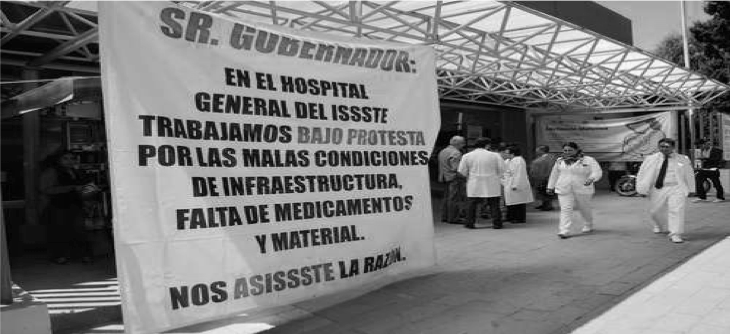

“The offer of services is insufficient to meet the local and regional demand. The capital’s hospitals have only 82 hospital and 13 intensive care beds to provide services to close to 6.5 million uninsured people in the metropolitan area. We have a mosaic of needs. Clusters should be created to form a regional network. The hospital network has a deficit of about 107 specialist physicians and 300 nurses. There is a lack of internists, emergency doctors, geriatricians, specialized nurses, but also, there is an excess of 310 generalists, 274 dentists and 197 social workers. There is also an incorrect distribution of staffing categories in shifts. There is an surplus of morning shift personnel and a deficit in the night shift. The problem is complex but we are trying to build consensus and to not violate labor rights. The lack of physicians also has something to do with absenteeism: there are up to 162 union commissioners among physicians and nurses” .

The López Obrador administration responds to the challenges of its metropolitan network with the Free Medical Services and Medicines Program aiming at “guaranteeing the population’s right to health protection with equity, understood as equal access to services under equal need, granting free medical services and medicines to the uninsured population with a minimum of three years of residence in the Federal District, as well as to adults older than 70 years of age, also residing in the DF”.

The Seguro Popular (Popular Health Insurance)

In matters of health, the administration of López Obrador coincides with the design and structuring of the most important federal program undertaken by the governing PAN: the Seguro Popular, which the GDF initially resists and in 2005, eventually adopts:

“The federal government and the capital’s government signed the agreement for the entry of the Seguro Popular into the capital. After three months of negotiations and debates a document was signed where the administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador agrees to absorb the cost of those that cannot pay a recovery fee to the health system. The Agreement for the Coordination of the Implementation of the Social Protection of Health System was signed by the National Commissioner of the Social Protection of Health, Juan Antonio Fernández, and the Secretary of Heath of the Federal District, Asa Cristina Laurell. The meeting took place and the agreement was signed in the office of the capital’s Secretariat of Health, without the presence of the press. The agreement establishes that the Seguro Popular will be applied gradually on 14.3 per cent of the population that is not affiliated to IMSS or ISSSTE. This social service will enter first in the Gustavo A. Madero and Iztapalapa delegations, both areas with high indexes of marginalization and indigenous population lacking social security. Under the agreement, the Seguro Popular will benefit families that are uninsured, have signed-up for the Liconsa milk program, and shall be exempt from paying the family fee because of their socio-economic conditions. Additionally, maximum priority shall be given to families of patients suffering invasive cervical cancer or linfoblastic lukemia, as well as those older tan 70 years of age that have cataracts. The Seguro Popular will apply starting in August and it is expected to serve 100 thousand of the poorest families living in the capital by the year’s end. The medical coverage of the Seguro Popular includes 154 interventions as listed in the Essential Services Catalogue of the Seguro Popular and the four interventions called “Catastrophic Spending”, as are invasive cervical uterine cancer, linfoblastic leukemia in those younger tan 18 years of age, intensive care for neonates, and ambulatory and antiviral treatments for HIV-AIDS. The capital’s government made clear that the services of the Seguro Popular would be delivered at accredited health centers and hospitals of the DF, and as a request of the federal Executive, the national referral hospitals shall participate in delivering secondary care interventions, once they become accredited. It stressed that the National Institutes of Health are not included in the agreement. The local administration said that it will continue the Program of free medical services and medicines for the uninsured families in a parallel fashion. The capital’s free program offers to the uninsured population, at no cost, all the services rendered in the medical units of the Federal District Government and the medicines included in the institutional framework. It also established that the signing of the agreement fulfills the commitment made by the local mandatory, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, during the last meeting with the president of the Republic Vicente Fox Quesada, of introducing the program into the capital” .

As it could be expected, the tension in the health network grew immediately and the complaints from doctors and nurses about working conditions and the inability to care for “more demand” with the same resources generalized. The complaints incresed with the impact of the austerity programs.

But by 2006, the public hospitals of the DF were caring for 57 per cent of the population, while the Seguro Popular reached barely 2 per cent.

“What do the residents of the DF do in case of illness? The greater majority (57 per cent) go to the doctor, hospital or clinic of the public sector. They also go to health services in the private sector (35 per cent), homeopathic doctor (2 percent), use home remedies (1 percent) or self-medicate (1 percent). Most users of health services go to IMSS (51 per cent), ISSSTE (15 per cent), hospitals of the DF (14 percent), health centers (11 per cent) or to the recently created Seguro Popular (2 per cent). However, although most resort to the public health service, that service is rated worse with a grade of 7.6 while the private service obtained 8.6. Besides being evaluated worse, most users of the public health service (61 per cent) considered the waiting time to be exaggerated while the majority (75 per cent) felt it was fair in the private sector. The care received, the state of the facilities, and the adequacy of the diagnosis and treatment were evaluated as good by the majority whether it being a public or private service. However, in all these cases the good evaluation was always higher for private services. Therefore is not surprising that 48 per cent of the users of public services had resorted sometime to the private sector seeking a better service (23 per cent), in case of emergency (20 per cent), to have less waiting time (13 per cent), because they open every day (5 per cent), or because there is no lack of medications (5 per cent). The users of private medical services go to their private physician, but there is a noticeable 6 percent that resort to the (walk-in) doctors of the Farmacias de Similares. In general users of the private health sector believed the price paid was fair but to an almost 30 per cent it seemed excessive. Moreover, most of them lack health insurance so they had top pay the service fee in full. In some times, users have opted for the private sector because of the severity of the illness (32 per cent), economic reasons (28 per cent), in case of emergency (19 per cent) or the service’s convenience (8 per cent). But in general, those that can afford private service maintain the public one as a second option .

Despite initial resistance to the Seguro Popular, López Obrador’s successor Alejandro Encinas, acknowledged the federal government in the person of President Fox while conducting an assessment of the progress made with the Seguro Popular:

“It should be noted that these programs are mutually beneficial, but the design of the program, its resources, much of the implementation rests with the federal government, and we will continue to fulfill the commitment that we signed in that agreement on this issue, the federal and the DF governments must walk together. We will continue to work in both areas. The government of the city has its own program of free medical services and medicines, which has 750,000 beneficiaries enrolled .”

If during the Cárdenas administration innovation was conspicuous by its absence, the period of López Obrador confirmed that in public administration, the most effective route to ensure the sustainability of new programs, in this case the Free Medical Services and Medicines Program, was to ensure that -both in its design and operation- a healthy balance is preserved between the routine work of the operators with proven expertise in the health network and the informed enthusiasm of the innovative talents pushing these emerging programs.

Marcelo Ebrard (2006-2011)

The evidence that the PRD administrations of the 1997-2011 cycle lacked proposals and programs to match the size, importance, and weight of the entity was reinforced with this administration.

The Ebrard government moves toward the political center and adopts strategies of subrogation of services, public-private partnerships and the outspoken support of private investment as a pivot of funding for the expansion of the capital’s infrastructure.

Ebrard’s control of the Delegations is the lesser in the period that the left has ruled. And in health, its management coincides with the design and implementation of

Calderón’s Health Insurance Program for a New Generation, a continued expansion of Fox’s Seguro Popular.

Ebrard faces the challenges of his metropolitan health network with the Angel Program of Health Care and Home Delivery of Free Medicines “as a groundbreaking move, a pioneer in its kind, to bring health to all residents of the capital, especially those who have less".

As said by the GDF:

“community educators and health promoters of the SSDF roam the highly marginalized areas to detect patients with conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, the elderly, the disabled, and pregnant women who require medical attention and medicines, but that because of their health condition, can not go to a hospital or health center to receive them. Later, doctors and nurses go to the home to provide care and bring medicines, as per the previously delivered prescription” .

Simultaneously, all the social programs laid by the predecessors of Ebrard are grouped into Angel Network which includes the following fifteen: economic support to persons with disabilities; health care and free medication delivery at home "Angel Program"; scholarships for children in social vulnerability; school breakfasts; guaranteed education; incentives for universal high school "Prepa Sí"; neighborhood improvement; improvement of housing; talented children; food pension for older adults; medical services and free medicines; free school uniforms; free school supplies; and overall housing.

By mid-2011, in the study Evaluation of programs and social policies in the DF, UNAM observed that:

"the elements analyzed in this assessment in relation to design, such as: the relevance of the actions proposed by the programs to address the problems identified, internal consistency, backing by a specific normative framework, appropriate mechanisms to achieve the objectives, and reports of progress, indicate that the DF has a model of care designed to assure the universal rights to health of the population without social security. In terms of program’s operation, they found it difficult to calculate the potential and target population, lack of statistical information regarding programs, and deficiencies in performance indicators and intended outcomes".

The separation of the substantial resources allocated to the local Secretariat of Health and Directorate General of Public Health Services of the DF -effect of the aforementioned decentralization of 1997- is severely affecting the consistency and comprehensiveness of its metropolitan health policies.

In February 2008 Manuel Mondragon y Kalb, then Ebrad’s secretary of health, boasted to have "corrected" the federal design of such decentralization.

He announced in September that Ebrard had considered fitting to "unite"-to the local secretariat under his responsibility- the services of epidemiology, vaccination, medical primary care, prevention and promotion programs of the Directorate General of Public Health, Decentralized Public Agency of the federal SSA. This, with the aim that the local Secretariat of Health can hold the stewardship of the sector and the "health project has only one head, one operational base and a single frame of comprehensive planning”.

By the third quarter of 2011, there was no way to document the "progress" of such "integration .

Predominance of the Popular Health Insurance (Seguro Popular)

According to the Outcomes Report of January to June 2011 of the System of Social Protection in Health, Seguro Popular was scheduled to affiliate -during 2011- 2 million 746 thousand 801 people and hoped to transfer -during the year- a subsidy for 2, 799 millions of pesos consistent with the affiliation scheduled, an amount almost equivalent to the budget allocated that year to the Directorate of the Public Health Services of the DF, following the Decree of the

Federal Expenditures of the DF for Fiscal Year 2011.

Budget woes and failures of coverage

In presenting his First Work Report, Armando Ahued, the second secretary of health for the Ebrard administration, had to acknowleged that:

“The Secretariat drags a budget deficit since 2008, meaning nearly 85.5 percent of approved expenditures for the year due to the passage of new laws and the operation of 10 official programs. The financial situation worsened with the Influenza A (H1NI) emergency, thus calling for the creation of a fund for prevention and care of contingencies. Among the programs facing economic difficulties are Angel, bariatric surgery, cataract surgery, and the HPV vaccine, among others. Equally weighing down is the implementation of the newly approved laws that lack a budgetary allocation, as are legal abortion, protection of non-smokers, Will Advance, and Transplant Center” .

A diagnosis of the Commission on Population and Development of ALDF conducted in 2011 noted that four of every 10 capital dwellers lacked access to social security. Two delegations: Iztapalapa and Gustavo A. Madero, concentrate about 40 percent of that citizenry in such conditions of social abandonment. Of the 8 million 800 thousand inhabitants of Mexico City, 3 million 700 thousand are without IMSS, ISSSTE, GDF social services, or other protective system. The uncovered totality reaches 43 percent. 900 thousand people in Iztapalapa and 500 thousand in Gustavo A. Madero. The diagnosis of the Commission concluded that “the right to health is a social right, and its constitutional consecration becomes a rhetorical statement if the State does not have sufficient resources to meet this obligation”.

Even Armando Ahued, claimed that the economic crisis had increased the demand for health services to 30 percent, and that it had been necessary to build three hospitals and expand hours of operation:

“We have work overload. Many people who previously relied on private hospitals now, with the costs of medical care, go to the public sector. And despite the efforts of by physicians prompt attention can not be given. I requested to the ALDF additional resources (2011) of 5 thousand 500 millions of pesos to maintain and develop infrastructure”.

The users’ voice

While inaugurating the first phase of the Regional General Hospital of Iztapalapa, Ebrard heard:

"claims from neighbors who demanded to be treated ‘as people, not animals’, for what he offered ‘I’m going to send a brigade from my office which will be here every day overseeing that you are treated well, and whoever does not treat you well, I will admonish’” .

A Healthy Municipalities Network in the 16 delegations?

In April of 2010 Ebrard announced the creation of:

"A Healthy Municipalities Network intended to make the health system in Mexico City evolve to meet several objectives such as changing health patterns rooted in society, specifically developed in accordance with local characteristics and to make the local health system more effective than it presently is. The first step was taken when the 16 delegational leaders suscribed to the formation of a network in order to advance in the mid-term health services that are more specific and effective" .

A Constitution for “the future” of the City?

Clearly, after 14 years of PRD governments in the GDF and despite their absolute majorities in the legislative ALDF, leftist governments have yet to hold a broad public debate focused on the political statute that given its importance and weigh on the federation, holds the DF.

On August 10, 2011GDF Ebrard asked the Senate to:

“Promote the adoption of the Constitution of Mexico City, as the nation’s capital not only should regain its name, because we are not a district, but also its full rights, and to have a Constitution. It is essential to the future of Mexico City” .

This has delayed in time the awaited improvement of its public policies, notably among them, that of health and social security.